Sunday, April 30

Do you like short films?

I'm not as loyal an attendee of SF Cinematheque's Sunday screenings at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts as I wish I were, but I've at least become a loyal viewer of the 45-year-old institution's annual co-presentations of programs of "avant-garde" shorts with the SFIFF. I just returned from seeing the Fugitive Prayers program curated by the Cinematheque's Irina Leimbacher and Kathy Geritz of the PFA, where the program plays again on Tuesday, May 2. The nine selections included three 35mm prints, three on 16mm, and three video works, a heartening development for film purists after last year's Count Down program only included one non-video presentation, Jim Trainor's wryly disturbing upending of the "cartoon animal" trope Harmony. This year's program is perhaps a little more serious, a little less Playful. The most downbeat of the films was also the shortest at four minutes, and probably the most politically topical right now: Dolissa Medina's 19: Victoria, Texas, which puts its audience through a disorienting and assaulting video recreation of what has been called the "worst immigrant tragedy in American history." This is the second of Medina's films to play this year's festival, as her Cartography of Ashes launched the SFIFF's Satellite Venue series when it was projected onto a Frisco fire station training tower April 21.

I'm not as loyal an attendee of SF Cinematheque's Sunday screenings at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts as I wish I were, but I've at least become a loyal viewer of the 45-year-old institution's annual co-presentations of programs of "avant-garde" shorts with the SFIFF. I just returned from seeing the Fugitive Prayers program curated by the Cinematheque's Irina Leimbacher and Kathy Geritz of the PFA, where the program plays again on Tuesday, May 2. The nine selections included three 35mm prints, three on 16mm, and three video works, a heartening development for film purists after last year's Count Down program only included one non-video presentation, Jim Trainor's wryly disturbing upending of the "cartoon animal" trope Harmony. This year's program is perhaps a little more serious, a little less Playful. The most downbeat of the films was also the shortest at four minutes, and probably the most politically topical right now: Dolissa Medina's 19: Victoria, Texas, which puts its audience through a disorienting and assaulting video recreation of what has been called the "worst immigrant tragedy in American history." This is the second of Medina's films to play this year's festival, as her Cartography of Ashes launched the SFIFF's Satellite Venue series when it was projected onto a Frisco fire station training tower April 21. Contrasting Medina's sorrowful tone was Nancy Andrews' 16mm tour-de-force of chalkboard animations, marionettes and shadow puppets, outdoor photography and "Black Maria"-style presentations, Haunted Camera. This 30-minute film sounds like it could be a too-eclectic shorts program unto itself, but remarkably it feels unified, largely by the presence of Andrews' character Ima Plume, P.I. (public illustrator). It's not an entirely light-hearted film as Plume is investigating her own death, but it's the only one in the program to have elicited substantial audience laughter. Other films induced elation through sheer technical brilliance, such as Tomonari Nishikawa's Market Street. I'd actually seen and liked this film before, at a Market Street-themed film event put on last September by the Exploratorium. But the outdoor projection at that event was not ideal for observing Nishikawa'a breathtaking organization of the hundreds (or was it thousands?) of photographs he took of Frisco's aorta. As he constructs his film frame-by-frame a constant attention to the lines, shapes and patterns defined by the underexposed and overexposed parts of each photo creates a fluid motion: squares moving in circles, diagonals working their way around a 360 degree axis, all built out of these familiar-looking stills. I can't think of a more visual satisfying tribute to a street I know so well.

Contrasting Medina's sorrowful tone was Nancy Andrews' 16mm tour-de-force of chalkboard animations, marionettes and shadow puppets, outdoor photography and "Black Maria"-style presentations, Haunted Camera. This 30-minute film sounds like it could be a too-eclectic shorts program unto itself, but remarkably it feels unified, largely by the presence of Andrews' character Ima Plume, P.I. (public illustrator). It's not an entirely light-hearted film as Plume is investigating her own death, but it's the only one in the program to have elicited substantial audience laughter. Other films induced elation through sheer technical brilliance, such as Tomonari Nishikawa's Market Street. I'd actually seen and liked this film before, at a Market Street-themed film event put on last September by the Exploratorium. But the outdoor projection at that event was not ideal for observing Nishikawa'a breathtaking organization of the hundreds (or was it thousands?) of photographs he took of Frisco's aorta. As he constructs his film frame-by-frame a constant attention to the lines, shapes and patterns defined by the underexposed and overexposed parts of each photo creates a fluid motion: squares moving in circles, diagonals working their way around a 360 degree axis, all built out of these familiar-looking stills. I can't think of a more visual satisfying tribute to a street I know so well. I feel Nishikawa's film should be considered an example of animation, even though he used no hand-drawn images. In a way it's not so fundamentally different from the work of animator Stacey Steers, who used very little of her own drawing in her film Phantom Canyon. The latter falls into the genre of cut-out animation festgoers were exposed to a few evenings earlier when the great Deerhoof accompanied Harry Smith's Heaven and Earth Magic at the Castro, variants of which also are found in the festival's Drawing Lines program of animated grotesqueries (in the Mysterious Geographic Explorations of Jasper Morello and Cosmetic Emergency). Other more well-known practitioners have included Terry Gilliam and even Steers' fellow Coloradoans Trey Parker and Matt Stone. Phantom Canyon is far more artful than "South Park", approaching the elegance of a Larry Jordan film like Our Lady of the Sphere but with more visually evident dexterity to the animation (whether this is a result of tools, talent, or tenaciousness or is simply an aesthetic choice, I have no basis to speculate). As Steers manipulates drawings from Edward Muybridge's studies of human and animal movement to simulate the motion Muybridge captured on camera at the dawn of cinema, Nishikawa manipulates the images captured by his camera to simulate an abstract motion of form. They are both a sort of collage artist, even if their materials, working methods, and finished products are vastly different.

I feel Nishikawa's film should be considered an example of animation, even though he used no hand-drawn images. In a way it's not so fundamentally different from the work of animator Stacey Steers, who used very little of her own drawing in her film Phantom Canyon. The latter falls into the genre of cut-out animation festgoers were exposed to a few evenings earlier when the great Deerhoof accompanied Harry Smith's Heaven and Earth Magic at the Castro, variants of which also are found in the festival's Drawing Lines program of animated grotesqueries (in the Mysterious Geographic Explorations of Jasper Morello and Cosmetic Emergency). Other more well-known practitioners have included Terry Gilliam and even Steers' fellow Coloradoans Trey Parker and Matt Stone. Phantom Canyon is far more artful than "South Park", approaching the elegance of a Larry Jordan film like Our Lady of the Sphere but with more visually evident dexterity to the animation (whether this is a result of tools, talent, or tenaciousness or is simply an aesthetic choice, I have no basis to speculate). As Steers manipulates drawings from Edward Muybridge's studies of human and animal movement to simulate the motion Muybridge captured on camera at the dawn of cinema, Nishikawa manipulates the images captured by his camera to simulate an abstract motion of form. They are both a sort of collage artist, even if their materials, working methods, and finished products are vastly different. Bill Morrison, whose feature Decasia was my favorite discovery of the 2002 SFIFF, is a collage artist known for working with the distressed images he finds in film archives. His latest, How to Pray, is part of a trilogy premiering in full at the current Tribeca Film Festival. In this 11-minute installment the grain-rich images of icebergs floating in the North Atlantic, sleek as a porpoise's skin, are actually less distressed than distressing, as they can't help but bring to mind the melting of polar caps and global warming brought on by increased petrochemical consumption (a development perhaps paralleled in the film industry when the kind of celluloid film stocks these icebergs were surely filmed with were replaced by the polyester Morrison's 35mm festival print is most likely made from). Or perhaps I was mostly distressed by composer David Lang's ominous alternating power chords.

Bill Morrison, whose feature Decasia was my favorite discovery of the 2002 SFIFF, is a collage artist known for working with the distressed images he finds in film archives. His latest, How to Pray, is part of a trilogy premiering in full at the current Tribeca Film Festival. In this 11-minute installment the grain-rich images of icebergs floating in the North Atlantic, sleek as a porpoise's skin, are actually less distressed than distressing, as they can't help but bring to mind the melting of polar caps and global warming brought on by increased petrochemical consumption (a development perhaps paralleled in the film industry when the kind of celluloid film stocks these icebergs were surely filmed with were replaced by the polyester Morrison's 35mm festival print is most likely made from). Or perhaps I was mostly distressed by composer David Lang's ominous alternating power chords. The Cinematheque also co-presented the SFIFF's Circles of Confusion program, which had a few standouts as well. First among them was Peter Tscherkassky's Sergio Leone resculpt, Instructions For a Light and Sound Machine, which I'd seen earlier this year at the PFA, but Cathy Begien's split-screen collaborative diary Relative Distance and Amy Hicks' also split Suspended 2 (pictured) tickled my fancy too. And Jay Rosenblatt's Afraid So left me with lots more questions to ponder than a 2.5-minute film usually does, not the least of which is: was Garrison Keillor's participation in this project as consensual and involved as his participation in this Thursday's closing film a Prairie Home Companion, or did Rosenblatt just tape Keillor off of the Writer's Almanac, make the film, and ask questions later?

The Cinematheque also co-presented the SFIFF's Circles of Confusion program, which had a few standouts as well. First among them was Peter Tscherkassky's Sergio Leone resculpt, Instructions For a Light and Sound Machine, which I'd seen earlier this year at the PFA, but Cathy Begien's split-screen collaborative diary Relative Distance and Amy Hicks' also split Suspended 2 (pictured) tickled my fancy too. And Jay Rosenblatt's Afraid So left me with lots more questions to ponder than a 2.5-minute film usually does, not the least of which is: was Garrison Keillor's participation in this project as consensual and involved as his participation in this Thursday's closing film a Prairie Home Companion, or did Rosenblatt just tape Keillor off of the Writer's Almanac, make the film, and ask questions later?Wednesday, April 26

Adam Hartzell on Kim Longinotto

The SFIFF is coming up on its midway point, and I've been availing myself of its varied opportunities, whether to stargawk at Factotum's Matt Dillion or to try to wrap my head around the Wayward Cloud. To briefly catch up on the press screenings I've been able to attend, I found Ricardo Benet's SKYY Prize contender News From Afar (which plays Apr. 29 and May 2) to be a very worthy and cinematic drama, constrasting the desolate beauty of a drought-plagued region of rural Mexico against the visual poverty of a gray and oppressive Mexico City. The documentary Favela Rising (plays Apr. 29 and May 1), on the other hand, fails to wade through its own audiovisual disorganization to show us more than snippets of its subject, Rio's socially-constructive musical group AfroReggae. And this morning I caught another doc, Adrian Belic's Beyond the Call (plays Apr. 30 and May 4), which I thought could have benefitted from some context beyond its narrow focus but still successfully parachuted me into the world of these three humanitarian adventurers for 82 minutes.

The SFIFF is coming up on its midway point, and I've been availing myself of its varied opportunities, whether to stargawk at Factotum's Matt Dillion or to try to wrap my head around the Wayward Cloud. To briefly catch up on the press screenings I've been able to attend, I found Ricardo Benet's SKYY Prize contender News From Afar (which plays Apr. 29 and May 2) to be a very worthy and cinematic drama, constrasting the desolate beauty of a drought-plagued region of rural Mexico against the visual poverty of a gray and oppressive Mexico City. The documentary Favela Rising (plays Apr. 29 and May 1), on the other hand, fails to wade through its own audiovisual disorganization to show us more than snippets of its subject, Rio's socially-constructive musical group AfroReggae. And this morning I caught another doc, Adrian Belic's Beyond the Call (plays Apr. 30 and May 4), which I thought could have benefitted from some context beyond its narrow focus but still successfully parachuted me into the world of these three humanitarian adventurers for 82 minutes. The SFIFF can't be beat this week and next in terms of variety and in-person appearances, but Frisco theatres have stepped up with some formidable counter-programming. The Red Vic has the City of Lost Children tonight and the Passenger Sunday-Monday. The Lumiere has the Fallen Idol for a week starting Friday. The Castro has booked a Stanley Kubrick series this Saturday-Wednesday. And on Monday night before heading to the Edinburgh Castle for International Remix I dropped in to see Barbary Coast, playing as part of the Balboa's Reel SF series that ends tomorrow.

On Friday the Balboa will be starting a week-long run of Kim Longinotto's latest documentary Sisters in Law. (It's the kickoff of the brand-new Balboa calendar spotted around town, which also includes Mongolian Ping Pong starting May 26, a massive Boris Karloff tribute starting June 2, and Jean-Pierre Melville's Army of Shadows starting June 23.) I've never seen a Longinotto film before, but my friend and now three-time contributor to this blog, Adam Hartzell has seen several, thanks to the Pacific Film Archive (which incidentally has released its newest calendar, too). Here's Adam:

The day after booking my recent vacation itinerary, I realized my work had a vacation day the Friday of the week I returned. Immediately I kicked myself, because if I'd have known, I could have scheduled to spend more time in Bangkok visiting the Thai Film Archive under the guidance of my friend Noy Thrupkaew and I could have spent more time at the entire Women's Film Festival in Seoul (WFFIS) rather than just the first half. I eventually felt better when I realized my early return would enable me to see five of the films with Kim Longinotto at the Pacific Film Archives (PFA) that I have yet to see. An added extra was that the jetlag that was keeping me up until 3am came in handy for the 9pm screenings that my up-at-5am work life normally has me struggling to keep my eyes open through. Plus, this enabled me an opportunity to give Longinotto a copy of the WFFIS's program that the film she co-directed with Florence Ayisi, Sisters In Law, opened. Longinotto, much to my appreciation, greatly appreciated this gesture since she hadn't received a program yet from that festival.

As part of their Documentary Voices series at the PFA, curator Kathy Geritz was able to procure films with and attendance of Kim Longinotto as she travels throughout the United States promoting the release of Sisters In Law, the film she directed along with Florence Ayisi. Let me now clarify why I'm using the preposition 'with' rather than 'by', i.e., "films with Kim Longinotto". Longinotto sees her films as collaborations with all involved in the making of the film. More so, when she is working in a language other than English where a translator friend is such an active part of the filmmaking process, she feels uncomfortable in crediting only herself as the director. So she credits as co-directors those who have assisted her in filming via their tireless translation. (In the case of The Day I Will Never Forget (2002), a film I did not see about female circumcision, there were so many women assisting with filming and translating that it became indexically cumbersome to credit each one.) This respect for those working with her carries over to the compassion conveyed towards those individuals who agreed to have these intimate moments of their lives portrayed on screen.And intimate moments they are when we consider how much about Iran's day to day lives are kept from us, particularly from my fellow U.S. citizens presently as the prophet-complexed administration mis-ruling our country and their complicit media forces seek to justify their desire to bomb Iran because they have the most toys. The powers that corrupt know that if we were to touch on the daily lives of those they fiendishly desire to bomb, we would be even more unwilling to allow such an atrocity to happen than we already are. Both Divorce Iranian Style (1998) and Runaway (2001), each co-directed with Ziba Mir-Hosseini, allow us an opportunity to follow snippets of the lives of Iranian women as they wrestle with limitations in self-definition that the Iranian government imposes upon them. I think I have missed three opportunities to see Divorce Iranian Style and I was thankful to the PFA for providing me yet another chance. Under the Iranian government's interpretation of Islamic Law, a man can divorce his wife without cause, but a woman must have her husband's consent or prove his impotency, insanity, or financial instability. Longinotto and Mir-Hosseini follow the goings on in one particular family courtroom. Unhappy in their marriages for various reasons, we witness several women try to negotiate their way out of these relationships. We witness them plead, demand, haggle, acquiesce, confess and lie to the judges to find liberation from their societal constraints.

Several moments stand out during this powerful documentary. When the judge is asked by a 16 year-old who was married as a 14 year-old to a man who looks like he's in his mid-30's, at what age can a girl be legally married, one can see the serious discrepancies between the written, literal law and the law that feels right when he answers by saying she can be married when she reaches puberty, which can be as early as 9. Longinotto elaborated how she found the judge to be a sensitive, kind man who was often in conflict with the literal law and the unique situation each plaintiff presented. This is why Longinotto and Mir-Hosseini included images of him praying in between cases, because the judge would often need such moments of reflection after all the unsettling matters he must settle.

An Iranian friend of mine whom I told about this moment in the film provided a hopeful story that presents an Iran not as beholden to fundamentalism as is often presented to us. When a friend of hers returned to contest a land dispute, he found himself in a courtroom with a plaintiff who decided to simply read from the Koran, regardless of relevance to the case at hand, to demonstrate he is the more faithful Muslim over that of my Westernized friend's equally Westernized friend. The judge, a mullah like the judge in Longinotto's film, responded with utmost diplomacy, calling out the tactics of the plaintiff as insincere while still showing respect for the Koran by saying something along the lines of 'We appreciate your gesture, but in this court we don't trust those who quote the Koran a lot.' If only we saw more of that judge's emerging Iran in the corporatized U.S. media.

Or if only we saw more of the younger Iranian generation coming up, such as the young girl who is the daughter of one of the female clerks who comes to the court after she finishes her school day. There is a powerful moment in the film when she gets up onto the bench, demands silence, and proceeds to hold court by providing the most astute commentary provided throughout the whole film. She questions the make-believe real men in front of her, asking them why they are not kinder and more respectful of their wives. Never has the cliché 'out of the mouths of babes' been more poignant as this moment where a child presents a better understanding of the women's view than the male judges or female plaintiffs seem to at times.Runaway follows younger women who, like the older women (although some not that much older, some even younger) seeking divorce, have left their homes for various reasons, often because of abuse by parents or siblings. These runaways seek refuge in a shelter run by women where they can avoid the dangers of the street while efforts are made to re-connect these girls with their families. Although there appear to be avenues for the girls to escape from extremely violent or otherwise detrimental homes, the primary mission appears to be to eventually reconnect these girls with their respective families. One of the interventions involves telling the girls boogeyman stories about the violence that can happen to them out on the street. I'm sure these stories have some truth to them, but I would hope for greater feminist advocacy in this women's space than reinforcement of the patriarchy. A particularly harrowing moment is when an obviously drunk (or high) greatly older brother seeks to advocate for his sister's return as the mother and sister stand silent. The child appears quite discomforted by the scene. Later when she engages in a quick turnaround professing excitement to return home, serious doubts arise over this young girl's future. But the shelter workers have no other recourse outside of getting no-violence guarantees signed, since the law is clearly geared toward keeping families together even if detrimental to individual lives within those families.

Kim Longinotto's commentary before and after the screenings was the best I have heard in recent Q&As. I resoundingly concur with Lys Woods at Synoptique who notes Longinotto's "completely winning persona." Longinotto truly added a great deal to the experience of the viewings, offering fascinating asides, such as her respect for the judge and how they captured the powerful moment of the child playing judge in Divorce Iranian Style. Apparently the child was quite precocious, greatly wanting to be filmed. Longinotto and Zir-Hosseini tried to explain that they wanted to capture a moment as it happened, not something planned. Whether or not the young girl planned the moment at the judge's bench, she saw her moment when Longinotto and Zir-Hosseini finally captured the judge leaving. Confidently striding up to the bench, pounding her tiny, opened hand, she held court for future Iranians should they survive the lethal politics of the Cheney/Rove administration, as, if not clear enough already, I very much hope they do.

The first film Longinotto co-directed, Pride of Place (1976, co-directed with Dorothea Gazidis and where Longinotto is credited as 'Kim Longinotto Landseer', 'Landseer' being a name her father attached to falsely claim that they were related to the famous painter), involved returning to her public (what would be called a private school in the U.S.) boarding school in England. Encouraged by financial necessity to film in black and white, the economic resourcefulness brought an appropriate feel to the dingy, dark, hopelessly unnecessary feel of the school. When we see the headmistress yet again get nasty with the 'stupid' girls, telling them how they have wasted 10 or more minutes on locating someone's blazer, I wanted to scream out at the headmistress, 'No, lady, YOU are the one wasting time!' The girls seem to learn more during their chatting sessions around the classes than studying anything in class. In her commentary, Longinotto spoke of how she admired the rebels she found while filming, and it was the smoking in the woods scene that brought the rare smile found on my face while watching this film, my face otherwise resorting to contorting a grimace at how horrible, or a guffaw at how ridiculous, all the scolding was.An interesting aspect of Longinotto's commentary was that it provided emotional balance for me. After the two Iranian films, I found myself seeing rows of half empty glasses, lacking the hope I saw after the documentaries done in Japan. But Longinotto reassured me and the audience that there were women doing some amazing work within the constraining parameters. Equally, my half-full glasses were toppled somewhat by the additional information Longinotto provided regarding the documentaries made in Japan.

Dream Girls (co-directed with Jano Williams, 1993) follows the immensely popular Takarazuka Music School and Theater where the Japanese women reverse the Kabuki rule of men playing women characters. Here the women play women and men, and the women playing men are the most avidly followed by women audiences that sell-out most shows. We follow the hazing rituals of the first year that consists of OCD-esque cleaning rituals, walking around the room close to the walls, and opening the door ever so slightly to slip through. I must say that I was a bit prone to find rebellion where others might not in the actors on stage and in the audience watching them. I have been concerned about the recent denigrating commentary about the Japanese housewife fans of "Yonsama", South Korean actor Bae Yong-joon of "Winter Sonata", a South Korean TV serial immensely popular throughout Asia. Rather than showing teenage regression amongst these women fans of both Yonsama and the Takarazuka Theater, I'm wondering, when explored in-depth rather than from tired journalistic frames, if we might find something similar to what Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess, and Gloria Jacobs found in their essay "Beatlemania: Girls Just Want To Have Fun", arguing convincingly that "Beatlemania" provided a sexual outlet for emerging women whose society placed all responsibility for state-sanctioned chastity on them rather than their male counterparts. The de-individuation of the group permitted a space where a young woman "...who might never have contemplated shoplifting could assault a policeman with her fists, squirm under police barricades, and otherwise invite a disorderly conduct charge" (The Audience Studies Reader, Will Brooker and Deborah Jermyn, p. 183). In the case of Dream Girls, might these fans and participants relish this space to expand beyond the gender roles they are confined within, where, for a moment, the women can have the privileges of men and these women as men can both caress and romance the women as they desire to be caressed and romanced? Might these women simply need a space away from men portraying men where they can talk amongst themselves about feelings and thoughts they feel they must hide elsewhere? And to bring this closer to my home, might we find similarities between Japanese housewives and their 'hysteria' for Yonsama and the male players of the Takarazuka Theater and the popularity of "Desperate Housewives", most significantly popular in the States where sexually- and gender-repressing Christian Dominionists have the greatest sway? Repressing people's healthy desires leads to projection on some object and the de-individuation of the mob - so wonderfully outlined in the essay "My Crowd: Or, Phase 5: A report from the inventor of the flash mob" in the March 2006 issue of Harper's Magazine by Bill Wasik - allows for un-self-conscious release of that which is not permitted release elsewhere by society.

Longinotto, and astute audience members, put a bummer on my progressive buzz by reminding me of a few items the film notes. First off, the Takarazuka Music School and Theater was created, choreographed, and overall ruled by men. Second, it is these ruling men who have set the rule that each 'top star' (only a male role-player can be a 'top star') is only permitted a two year reign so as to reign in any feminist ideas she might get in her head from being a he for any longer. Not so ironically, male role-players are mythed within Japanese culture as desirable wives because they 'know' what it's like to be a man. So this most progressively possible of projects still ends up feeding the patriarchy's needs. Still, such spaces won't necessarily stay completely confined within the rules set by others. Gradually women demand similar freedoms men demand from the exhilarations provided by such alternative spaces. Some of them will go back to their home lives and enact positive changes of varying degrees through the inspiration provided by their top star muse.

All this could perhaps better explain the recent cultural shift in Japan that is unnecessarily disparagingly described as para-chan or "parasite singles", (a disparaging moniker chosen by a male sociologist, nonetheless). The phenomenon has been too often discussed as a 'problem' and the focus of this 'problem' has too often been mis-placed on the women alone rather than the political/economic/social factors that make it difficult for a single women to find work, a reasonable rent, and fulfilling relationships in Tokyo. Their only options are either staying with their parents or shacking up with a man to survive. (And in those latter cases, why aren't the men referred to as 'para-chans' since it can be well argued that the men are parasitic in their living off the unpaid labor of their wives? Yeah, we know why male sociologists never think of their fellow men that way.) For those women who want a job and relationship just like men, (or those women who find Japanese society too restrictive to allow for the open Lesbian relationship they desire), staying with their parents seems more palatable than solely tending house for a man they are less than happy with. The dreamspace provided by the Takarazuka Music School and Theater in Japan can't help but seep into our waking worlds as well. Could the phenomenon of Women Alone with Parents - allowing for a non-judgmental, thus more appropriate, term to describe this phenomenon in Japan - be the reasonable depressive response that follows the manic highs of the possible freedoms the Takarazuka Theater envisions? Could this just be the natural slacking when your hopes are squelched for a moment by economic and social inequality?

And might not that hope be found again in ones later years? Such as the hope I found in The Good Wife of Tokyo (co-directed with Claire Hunt, 1993). Kazuko Hohki is a Japanese woman living in Tottenham, England for over 15 years who has returned to her home with her three-person, art rock band Frank Chicken. (Recall David Byrne of the Talking Heads in his oversized suit chopping his forearm with his other hand while commenting on how this is not his beautiful house and tell him this is not his oversized suit either, take it off of him, and then put him in a skyscraper costume and make him sing and chant about the Rockefeller Tower being purchased by the Japanese. That is Frank Chicken.) Turns out Hohki's mother is quite an alternative performer as well, being a leader (with limits, which I'll get to later) in the House of Development, a Japanese mélange of Shinto, Buddhist, Christian, and Tony Robbinsist religions, a congregation of which she runs from her home. We see Hohki's mother minister to her disciples through their laughter and pain as her retired husband reads upstairs and Hohki remembers why she left Japan. I found both Hohki and her mother resilient souls who negotiated different spaces for similar needs to express themselves. Longinotto somewhat tempered the hope I found by adding that the House of Development is run by men and they are the ones who put a stop to Hohki's mother's special leaflet dance displayed during the credits. Plus, Longinotto underscored the moments in the film where Hohki's mother advocates acceptance of a women's plight advised by much of the House of Development's tenets that raze the more fulfilling houses that would otherwise develop were we left to negotiate homes that allowed for more gender equality.What Longinotto's commentary on both perspectives of the quintessential glass of half water underscores is that each of her films are full of more than we think, positively and negatively. So when those of us in San Francisco head out to see Sisters In Law at the Balboa after eating the fabulous food at the Shanghai Dumpling King and then contemplating the rulings of the Cameroonian Judge Beatrice Ntuba and what they mean for women, men, Muslims, Africa, and the world over coffee at Cafe Zephyr across the street afterwards, keep in mind there is so much more to this story than we will ever know. (Just as there's so much more to enjoy about The Richmond District than the three establishment shoutouts I've made.) We just can't stop with this documentary in hearing, seeing, and experiencing more about our mutual worlds. Longinotto isn't going to stop making these films with women, and I don't see myself ever getting tired of watching them.

Saturday, April 22

Date movies?

As Karl Marx once said that religion is the opiate of the masses, Philippe Garrel might say that opium is the opiate of bourgeois revolutionary artists. Garrel, perhaps most famous in general circles for his relationship with Nico, is the director of the Regular Lovers, a three-hour recollection of the events of French May and its aftermath as reflected in the lives of a young poet François (played by Garrel's son Louis) and his friends. I saw the film last night at a SFIFF screening (it plays again April 23 and 29). Festival director Graham Leggat succinctly introduced the film (after apologizing for the delay created by a last-minute decision to play it in two of the Kabuki's houses using interlocked projectors, to the relief of the folks with bad seats who were able to move to the other theatre) as "astringent" and "challenging", but I did not expect it to approach a Bela Tarr level of challenge (and reward), as it did in the wordless long-take chaos of the police vs. rioters sequence that makes up most of the first hour of the film. The trajectory of François from defiant young radical eager to call the bluff of The Establishment, to 20-year-old burnout, is clearly Garrel's parallel for his generation's political direction after May 1968. Blackened from the burning of automobiles and chased to the rooftops by the Paris cops, he is refused sanctuary by the average French citizen but eventually accepted by a hedonistic young patron of artists and drug connections named Antoine. Antoine is amiable to the idea of revolution but would rather drive a Jaguar than turn one on its side and use it as a barricade. He "doesn't believe in human generosity" but offers his cash, his home, and hits from his opium pipe to friends until they refuse, as François' fellow radical Jean-Christophe eventually does, one at a time.

As Karl Marx once said that religion is the opiate of the masses, Philippe Garrel might say that opium is the opiate of bourgeois revolutionary artists. Garrel, perhaps most famous in general circles for his relationship with Nico, is the director of the Regular Lovers, a three-hour recollection of the events of French May and its aftermath as reflected in the lives of a young poet François (played by Garrel's son Louis) and his friends. I saw the film last night at a SFIFF screening (it plays again April 23 and 29). Festival director Graham Leggat succinctly introduced the film (after apologizing for the delay created by a last-minute decision to play it in two of the Kabuki's houses using interlocked projectors, to the relief of the folks with bad seats who were able to move to the other theatre) as "astringent" and "challenging", but I did not expect it to approach a Bela Tarr level of challenge (and reward), as it did in the wordless long-take chaos of the police vs. rioters sequence that makes up most of the first hour of the film. The trajectory of François from defiant young radical eager to call the bluff of The Establishment, to 20-year-old burnout, is clearly Garrel's parallel for his generation's political direction after May 1968. Blackened from the burning of automobiles and chased to the rooftops by the Paris cops, he is refused sanctuary by the average French citizen but eventually accepted by a hedonistic young patron of artists and drug connections named Antoine. Antoine is amiable to the idea of revolution but would rather drive a Jaguar than turn one on its side and use it as a barricade. He "doesn't believe in human generosity" but offers his cash, his home, and hits from his opium pipe to friends until they refuse, as François' fellow radical Jean-Christophe eventually does, one at a time. François never does and inevitably it leads to his destruction. The revolutionary dream disappearing with barely a whimper. Garrel's metaphors are perhaps too neat and telegraphed with too much advance warning. But his foreboding foreshadows, combined with the sense of visual authenticity lent by crisp black-and-white photography reminiscent of nouvelle vague films or sometimes even an Andy Warhol Screen Test, rewrite the more common narrative associated with the era ("we thought we would change the world") with a fatalistic, pessimistic brush. The chief enigma of the film for me is the basis for the film's title. A great deal of the Regular Lovers follows François' romance with a gleaming-irised sculptor named Lilie (Clotilde Hesme), and while the scenes of Hesme and the young Garrel together have a wonderful naturalism to them, after a single viewing I'm unclear what Lilie really means for François; is she another distraction from the revolutionary path, or the last available life preserver on a ship sinking into an opium haze? Or both? In either case, the lovers' scenes often felt completely disconnected from the rest of the story.

With a visually stunning film like the Regular Lovers I don't consider this a complaint or criticism as much as a subject for further investigation, should I ever have the chance to see it again, which I doubt given the film's length and lack of commercial appeal. It's exactly the kind of film I'm thrilled to see at the festival. Unlike one of the films I caught at a SFIFF press screening, the Hungarian (but in no way reminiscent of Bela Tarr) See You in Space. If the love story was the least satisfying element of the Regular Lovers for me, at least it was part of a bold and unique film. See You in Space contains unsatisfying love stories too, at least four of them. But it tries to mask its shallow treatment of each by cutting back and forth between each of them as if it were the Budapest version of Crash (complete with contrived miracles, and even one uncomfortable scene that reinforces racial stereotypes while trying to scold them). In a way it's the perfect "date movie" for a couple looking to see a slightly cultured film that's about as aesthetically un-challenging as they get, and have an excuse to launch a discussion of their relationship afterward (because I don't think a discussion of the film itself is likely to last much more than a few minutes). Doesn't really matter what kind of relationship, as the film makes sure to superficially touch on all the main ones: long-distance (a cosmonaut and a dancer), age disparate (a hairdresser and her customer/victim), professionally forbidden (a psychologist and her patient), unfaithful, interracial, etc. And maybe there's nothing wrong with a "date movie" like See You in Space being part of the festival (it plays April 27, May 2 and May 4). I just wish I hadn't unwittingly picked such a clunker as one of my few luck-of-the-draw press screening experiences.

With a visually stunning film like the Regular Lovers I don't consider this a complaint or criticism as much as a subject for further investigation, should I ever have the chance to see it again, which I doubt given the film's length and lack of commercial appeal. It's exactly the kind of film I'm thrilled to see at the festival. Unlike one of the films I caught at a SFIFF press screening, the Hungarian (but in no way reminiscent of Bela Tarr) See You in Space. If the love story was the least satisfying element of the Regular Lovers for me, at least it was part of a bold and unique film. See You in Space contains unsatisfying love stories too, at least four of them. But it tries to mask its shallow treatment of each by cutting back and forth between each of them as if it were the Budapest version of Crash (complete with contrived miracles, and even one uncomfortable scene that reinforces racial stereotypes while trying to scold them). In a way it's the perfect "date movie" for a couple looking to see a slightly cultured film that's about as aesthetically un-challenging as they get, and have an excuse to launch a discussion of their relationship afterward (because I don't think a discussion of the film itself is likely to last much more than a few minutes). Doesn't really matter what kind of relationship, as the film makes sure to superficially touch on all the main ones: long-distance (a cosmonaut and a dancer), age disparate (a hairdresser and her customer/victim), professionally forbidden (a psychologist and her patient), unfaithful, interracial, etc. And maybe there's nothing wrong with a "date movie" like See You in Space being part of the festival (it plays April 27, May 2 and May 4). I just wish I hadn't unwittingly picked such a clunker as one of my few luck-of-the-draw press screening experiences.Thursday, April 20

It's here

Yesterday I was browsing the New Book section at A Clean Well-Lighted Place For Books and couldn't resist paging through Lonely Planet's latest coffee table ornament the Cities Book, which ranks 200 of the world's cities on some uncertainly scientific criteria that I neglected to notice. Coming in at number seven, just behind Paris, New York, Sydney, Barcelona, London and Rome (with Bangkok, Cape Town, and Istanbul rounding out the top ten) was my beloved Frisco. From my bookstore-browse-mode glance, I found three mistakes on my city's page, though. First, the repetition of the myth that residents never "call it Frisco". Second, Memento was for some reason among the half-dozen or so films listed as set here (and none of these were.) Third, no mention was made in the "strengths" column or anywhere else I noticed of the city's almost constant parade of excellent film festivals, including the first, largest, most broadly-programmed one: the SFIFF, which begins this evening with a Castro screening of Perhaps Love and runs for two weeks.

Yesterday I was browsing the New Book section at A Clean Well-Lighted Place For Books and couldn't resist paging through Lonely Planet's latest coffee table ornament the Cities Book, which ranks 200 of the world's cities on some uncertainly scientific criteria that I neglected to notice. Coming in at number seven, just behind Paris, New York, Sydney, Barcelona, London and Rome (with Bangkok, Cape Town, and Istanbul rounding out the top ten) was my beloved Frisco. From my bookstore-browse-mode glance, I found three mistakes on my city's page, though. First, the repetition of the myth that residents never "call it Frisco". Second, Memento was for some reason among the half-dozen or so films listed as set here (and none of these were.) Third, no mention was made in the "strengths" column or anywhere else I noticed of the city's almost constant parade of excellent film festivals, including the first, largest, most broadly-programmed one: the SFIFF, which begins this evening with a Castro screening of Perhaps Love and runs for two weeks.Being big and broadly-programmed is wonderful, but it's not without it's drawbacks. It may be getting harder to bring film lovers with increasingly stratified tastes together in quantities large enough to fill venues like the Castro and Kabuki's House 1, but the SFIFF somehow manages it (fairly well, as there are already a good dozen films at "Rush Status" including the Castro closer A Prairie Home Companion). It does it in part by making selections that exhibit a diversity of virtues; some films are broadly entertaining, others are politically or otherwise deeply thought-provoking. Some are of a high technical quality, and others display a corner of the planet that's overlooked, inherently fascinating, or both. Some break new aesthetic ground for the motion picture form, and others shed light on the career of an important filmmaker in the context of his or her other works. In fact, the majority of films I've seen at this festival over the years exhibit more than one of these virtues, and a great many exhibit all or nearly all of them.

My theory is that most fest-goers have one or two of these virtues (or others I've not thought of) in mind, consciously or not, as the primary criteria for judging the films they see, and if a particular selection comes up short in that regard they may hold it against the festival. If a ticket buyer fails to do more research on a film selection than reading the short description in the miniguide, the potential for this kind of reaction is exacerbated. Thus, the subtle perception that there's some kind of problem with the festival programming is able to take hold.

Of course, it's not all that easy to do research on a film to know how thought-provoking or how groundbreaking it's going to be before you see it, especially considering that these are rather subjective qualities. Which is probably why my first instinct is to fall back on the much-easier-to-discern "how many films are by a filmmaker I've appreciated before" criterion for evaluating the festival, even before I've seen any of them. There's a small-minded part of me that wishes the SFIFF would become an annual showcase for all the new films released by directors whose past films I've liked. But this sort of daydreaming fails to hold up under any scrutiny, as A) it would lead to a certain calcification, and B) I'd miss out on the experience of going into a film with little to no expectations and being completely won over, as I was last year with Sumiko Haneda's Into the Picture Scroll or with Marie de Laubier's Veloma a few years back. Would I even notice the absence of Hong Sang-soo's a Tale of Cinema from this year's program if not for having almost blindly stumbled into Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, my doozy of an introduction to Korean cinema, in the 2001 edition of the festival?

Ultimately, I just have to trust the programming staff to some degree when I pull together a schedule of films that balances those by favorite auteurs with unknown quantities that lead me down unexpected paths of cinematic exploration. And then there's always the press to help with the narrowing-down process. This year there is a lot of advance coverage available on the web, thanks to a publicity department that doesn't treat the internet as a third-class media form. The last couple years they invited me to press screenings even though the wrap-ups I wrote for Senses of Cinema weren't published until well after the festival. This year my blog provides me a place to express my thoughts on some of the films before they play, and wouldn't you know it I've only been able to attend five, fewer than ever. I was particularly sorry for missing Half Nelson, the Dignity of the Nobodies and Play.

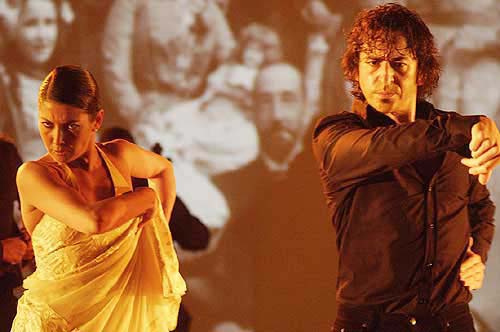

Of those I did see, a favorite was Carlos Saura's Iberia (which plays April 21, 23, 25 and 27 at the festival). If it seems predictable that I would respond to the one by the director with the longest resume (reaching back into the 1950s), perhaps I should clarify that I've only seen one other of his films, the equally color-drenched and stylized Tango. In this case perhaps relative ignorance is an aid to appreciation, as more than one review I've read compares Iberia unfavorably to Saura's 1995 film Flamenco. If accurate, such a comparison makes me especially interested in investigating more of Saura's filmography, though I'm always apprehensive of such visually rich dance films surviving the shrink-down from cinema to even a larger-than-average television. Iberia is extremely visual; made up of seventeen performance pieces staged in combination with imaginative projections and lighting effects expressly for Saura's camera (or should I say for that of cinematographer José Luis López Linares) it contains no narrative beyond that of that found in each dance. What it does contain is a great deal of unbottled sexual tension that one sometimes can sense dancers exude when rhythmically locked to an attractive partner onstage, but that is so much more interesting to watch in the close-ups that only a camera can provide. And music; the film utilizes an assortment of very accomplished musicians playing traditional and contemporized arrangements from the Iberia Suite by Catalan pianist and composer Isaac Albéniz.

Of those I did see, a favorite was Carlos Saura's Iberia (which plays April 21, 23, 25 and 27 at the festival). If it seems predictable that I would respond to the one by the director with the longest resume (reaching back into the 1950s), perhaps I should clarify that I've only seen one other of his films, the equally color-drenched and stylized Tango. In this case perhaps relative ignorance is an aid to appreciation, as more than one review I've read compares Iberia unfavorably to Saura's 1995 film Flamenco. If accurate, such a comparison makes me especially interested in investigating more of Saura's filmography, though I'm always apprehensive of such visually rich dance films surviving the shrink-down from cinema to even a larger-than-average television. Iberia is extremely visual; made up of seventeen performance pieces staged in combination with imaginative projections and lighting effects expressly for Saura's camera (or should I say for that of cinematographer José Luis López Linares) it contains no narrative beyond that of that found in each dance. What it does contain is a great deal of unbottled sexual tension that one sometimes can sense dancers exude when rhythmically locked to an attractive partner onstage, but that is so much more interesting to watch in the close-ups that only a camera can provide. And music; the film utilizes an assortment of very accomplished musicians playing traditional and contemporized arrangements from the Iberia Suite by Catalan pianist and composer Isaac Albéniz. Hong Kong's Peter Chan is a director whose past work I've been impressed with (particularly his romantic ghost story Going Home) but his latest Perhaps Love, a musical produced in the wake of the popularity of the likes of Moulin Rouge and the Phantom of the Opera in Asian countries, is an unfocused, lame effort. It has nothing to do with any of the few Hong Kong-made musicals I've seen, whether Mambo Girl or Lady General Hua-Mulan or even the equally weak Dance of a Dream. Instead it tries hard to match the current Hollywood style but can't match the Baz Luhrmann level of opulence and ends up feeling mostly flat, particularly during the song-and-dance numbers, which is a bad sign in this genre. The script about a star director (Jacky Cheung) struggling to find his passion while making a circus movie feels over-calculated in its vaccine-like self-criticism, and quickly gets repetitive. Eventually I spent most of my mental energy trying to guess which scenes were shot by Chris Doyle and which by Peter Pau (the end credits provided my answer). You can take a guess which one of them shot the only scene I really liked in the film, a trapeze showstopper with Cheung and Zhou Xun. I suppose I should also mention that Takeshi Kaneshiro is in the film too, but frankly I'd rather not have to think of him wearing a stovepipe hat any longer. I applaud the SFIFF for picking an Asian film by an interesting auteur to open the festival. It's just too bad it's not a better film.

The other three films I saw at press screenings will have to wait until my next post for now; expect it soon. But in the meantime I should mention that two screenings of Masahiro Kobayashi's kidnap drama Bashing (April 21 & 23) have been cancelled and replaced by an additional one at the Kabuki on April 28th, and that Matthew Barney's Drawing Restraint 9 and a teasing first 20 minutes of Richard Linklater's a Scanner Darkly have also been added to the program at the Kabuki, on the evenings of April 26 and May 2, respectively.

Saturday, April 15

Ten Decades of Frisco in Film

In preparation for tomorrow's launch of the Balboa Theatre's Second Annual Reel San Francisco series of films from a diverse range of genres and time periods, all made in and/or about Frisco, as well as the Celluloid San Francisco book event at the Public Library next week, I present a list of some of the titles I think of first when I think of Frisco and film.

The post title is a bit of a misnomer, as Frisco Bay has been a motion picture hotbed for more than ten decades. It all began when Edward Muybridge first successfully photographed a horse's gallop for Leland Stanford in 1878. I've seen interesting Frisco films made in every decade since the Lumiere Brothers invented film exhibition in 1895, starting with 1897's Return of Lifeboat and including 1905's a Trip Down Market Street Before the Fire, which was shown at the PFA last weekend and I suspect might be among the films shown this Tuesday at 7PM as part of the Balboa's "City Quakes" earthquake centennial commemoration program. But I will start this list formally with the decade where films first grew to running times similar to those we expect today:

The post title is a bit of a misnomer, as Frisco Bay has been a motion picture hotbed for more than ten decades. It all began when Edward Muybridge first successfully photographed a horse's gallop for Leland Stanford in 1878. I've seen interesting Frisco films made in every decade since the Lumiere Brothers invented film exhibition in 1895, starting with 1897's Return of Lifeboat and including 1905's a Trip Down Market Street Before the Fire, which was shown at the PFA last weekend and I suspect might be among the films shown this Tuesday at 7PM as part of the Balboa's "City Quakes" earthquake centennial commemoration program. But I will start this list formally with the decade where films first grew to running times similar to those we expect today:

the 1910s: The Tong Man (William Worthington, 1919)

Japanese-American screen idol Sessue Hayakawa played a Chinese anti-hero in this studio set-bound and somewhat sensationalistic depiction of the Frisco Chinatown underworld. It's no masterpiece and I wonder if there was even a single ethnically Chinese actor or crewman on set (most or all the Chinese parts were played by Japanese or white actors, which was customary for the time period) who could speak up against the film's stereotyping. Still, it's a fascinating curio and Hayakawa gives a typically strong performance.

On my to-see wish list: the Chaplin Essanay film a Jitney Elopement.

the 1920s: Greed (Erich Von Stroheim, 1924)

the 1920s: Greed (Erich Von Stroheim, 1924)

Von Stroheim gained a reputation as one of the first advocates for film realism in large part through his desire to shoot his version of Frank Norris's novel McTeague in the Frisco where Norris had lived and, as Jonathan Rosenbaum points out, "scouted locations" for his story of a love triangle doomed by the sudden appearance of wealth. A masterpiece in its own right, Greed also feels like a primer on making Frisco locations (in this case the corner of Hayes and Laguna, the Cliff House, and dozens more) work to the advantage of a great film, one that surely influenced future directors trying the same trick like Orson Welles (see below). The studio cut (not Stroheim's original 47-reel version now lost, or Rick Schmidlin's digital "recreation") played the Balboa series last year.

On my to-see wish list: Lon Chaney surviving the Great Quake in the Shock.

the 1930s: San Francisco (W.S. Van Dyke, 1936)

I had never seen the most famous film about the 1906 Earthquake until the Balboa played it last April for the 99th anniversary of the event. Now it's being brought back April 16-18 for the 100th, and if you live in the area and have never seen it before you really ought to. Though this film, directed by Woodbridge Strong Van Dyke (aka "One Take Woody"), has a not wholly undeserved reputation for stodgily moralizing, it really is a grand entertainment nonetheless. I like to think of it as the movie that represents to Frisco what Gone With the Wind is for Atlanta: It's a big-budget, star-laden special effects extravaganza that distorts history through a potentially worrying lens, but it also treats The City as the center of the Universe. If you, like me, think of Frisco as a better candidate for that honor than Ted Turner's town, you'll almost certainly like San Francisco better than the even more famous picture Clark Gable made three years later. And perhaps this film's conservative reputation has been overblown too; the Terry Diggs piece I linked to convincingly argues that the film was covertly packed by screenwriter Anita Loos with pro-labor jabs against the MGM hegemony.

On my to-see wish list: the Howard Hawks Barbary Coast, which plays the Balboa on a bill with Pal Joey April 23-24.

the 1940s: the Lady From Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1947)

You may need to be automatically predisposed to Welles to be able to get over his silly brogue and fully enjoy this film, the only one he made with his then-wife Rita Hayworth, but there's no denying the power of the scenes that make use of some of the eeriest Frisco locations imaginable, now all the eerier because these places are no longer with us. I'm speaking particularly of Playland at the Beach, where this loopy noir ends in an especially bizarre fashion, and the murkily-lit halls of the recently demolished Steinhart Aquarium, where the (by this point in the Welles-Hayworth marriage) fictional-only lovers rendezvous and talk about a doubly-impossible future together. If the story doesn't totally hang together it certainly doesn't matter when Welles is making use of such dream-logic images as moray eels and funhouse mirrors to make an end run around the glib symbology often found in Hollywood classicism. I didn't see this film when it played in last year's Balboa series, but I've seen it several times, most memorably a few years ago at an outdoor screening in New York City's Bryant Park; admittedly this film is just as much a New York movie as a Frisco movie, but Frisco gets the last word.

You may need to be automatically predisposed to Welles to be able to get over his silly brogue and fully enjoy this film, the only one he made with his then-wife Rita Hayworth, but there's no denying the power of the scenes that make use of some of the eeriest Frisco locations imaginable, now all the eerier because these places are no longer with us. I'm speaking particularly of Playland at the Beach, where this loopy noir ends in an especially bizarre fashion, and the murkily-lit halls of the recently demolished Steinhart Aquarium, where the (by this point in the Welles-Hayworth marriage) fictional-only lovers rendezvous and talk about a doubly-impossible future together. If the story doesn't totally hang together it certainly doesn't matter when Welles is making use of such dream-logic images as moray eels and funhouse mirrors to make an end run around the glib symbology often found in Hollywood classicism. I didn't see this film when it played in last year's Balboa series, but I've seen it several times, most memorably a few years ago at an outdoor screening in New York City's Bryant Park; admittedly this film is just as much a New York movie as a Frisco movie, but Frisco gets the last word.

On my to-see wish list: I Remember Mama, based on the book I remember my mama reading to me as a kid.

the 1950s: Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

What to say about this film I often consider the greatest of all time? I've seen it too many times to be surprised by its basic plot structure like I was the first four or five times I saw it, always suckered in by the false first climax. But each time I'm still surprised by another Hitchcockian touch I notice, little things like how Pop Liebel's nostalgia for "the power and the freedom" associated with manhood helps Scottie give himself permission to resist the post-war modernization of gender relations and throw himself into an old-fashioned romantic melodrama. And I'm always struck by another glimpse of the Frisco that existed before I was born but am slowly trying to understand. I've had this site on my sidebar since starting this blog, and if you've never taken the time to lose yourself in it for a while, how about now?

On my to-see wish list: the National Film Registry-selected D.O.A., which plays at the Balboa with another noir, the Bigamist, April 25th.

the 1960s: the White Rose (Bruce Conner, 1967)

I first planned this list to be entirely made of feature films, but once I thought of this experimental documentary short, I had to bump the Birds (at the Balboa April 21-22) or Take the Money and Run (April 26-27) or whatever else I was considering for this decade. It's the first Bruce Conner film I ever saw, back in 1996 at the old DeYoung Museum when it was showcasing art of the Beats. The centerpiece of the exhibit was Jay DeFeo's painting/sculpture the Rose, which she applied 2,300 pounds of oil paint to over the course of eight years before removing it by forklift from her apartment at the Pacific Heights section of Fillmore Street. Conner lived nearby and was on hand to film the extraction, which he edited into this beautiful seven minute piece accompanied by music from Miles Davis's Sketches of Spain.

On my to-see wish list: Experiment in Terror, the classic Blake Edwards thriller I missed when the Balboa showed it last year.

the 1970s: the Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

This is another one of those films that I've seen so many times that it's seemingly seeped into my DNA, but that doesn't mean it's easy to know where to begin to talk about it. I might as well start where the film does, with Union Square, which in a single extended zoom shot morphs from a picturesque cityscape into a paranoia-inducing intrusion. The transformation seems oddly paralleled in the history of the location since Coppola's film was released; gradually the public square has felt more and more encroached upon by the neon-lit signs of the corporations that surround it, culminating in a recent remodel that has shifted the focus of the space toward the Macy's on its South side. I don't know all the locations used in the Conversation but I'm not sure I want to know either; the Cathedral Hill Hotel, which I pass nearly every day on the way to work, has felt just a little creepier since I realized it used to be called the Jack Tar Hotel and was the site of the film's most disturbing scene.

This is another one of those films that I've seen so many times that it's seemingly seeped into my DNA, but that doesn't mean it's easy to know where to begin to talk about it. I might as well start where the film does, with Union Square, which in a single extended zoom shot morphs from a picturesque cityscape into a paranoia-inducing intrusion. The transformation seems oddly paralleled in the history of the location since Coppola's film was released; gradually the public square has felt more and more encroached upon by the neon-lit signs of the corporations that surround it, culminating in a recent remodel that has shifted the focus of the space toward the Macy's on its South side. I don't know all the locations used in the Conversation but I'm not sure I want to know either; the Cathedral Hill Hotel, which I pass nearly every day on the way to work, has felt just a little creepier since I realized it used to be called the Jack Tar Hotel and was the site of the film's most disturbing scene.

On my to-see wish list: Time After Time starring Malcolm McDowell as HG Wells.

the 1980s: a View to a Kill (John Glen, 1985)

I never said these were "the best" films shot in Frisco, just the ones that for me feel the "Frisco"-est. But honestly the last of the many times I saw this film, probably when I was in ninth grade, I still loved it. I was just the right age for James Bond when it came out in '85, and I can't begin to convey the sense of civic pride I felt when I learned that the international playboy and super-spy was going to be coming to my town, which meant that I obviously lived in a location as exciting and exotic as India or the Bahamas. Opening weekend fell near my twelfth birthday, and my dad took me and a dozen buddies across the Golden Gate to the theatre in Corte Madera he liked to avoid the Frisco crowds at. This was my last birthday party at which I felt no sense of inadequacy for not feeling cool enough to invite girls. I was outwardly resisting my looming teenager-hood as strongly as I could (I didn't even really know who Duran Duran was, but I did like their theme song) and a View to a Kill was the perfect preadolescent fantasy to allow me to do that for another two hours, plus get a glimpse of Grace Jones's naked bum. But probably my favorite scene was the fire engine chase scene culminating in the nail-biter at the "Lefty" O'Doul Drawbridge. The insanity of Christopher Walken's Zorin dueling against Bond on top of the area's most famous bridge was just good gravy. Since my middle-school-age days of intense study of Bondology, I've come to learn that a View to a Kill is considered by most to be one of the worst films in the series. I suspect it's at least in part because it's the film which let Roger Moore beat David Niven in Casino Royale as the oldest actor ever to play James Bond (he turned 57 during filming). One of these days I'd like to revisit it and see what I think, but in the meantime I don't mind reliving the memories.

On my to-see wish list: Chan is Missing, another National Film Registry selection.

the 1990s: Chalk (Rob Nilsson, 1996)

Like the Tong Man and San Francisco, I've only seen this film (actually shot on video) once but it left a powerful impression and turned me into a real Rob Nilsson admirer. Nilsson's Cassavetes-influenced filmmaking style cuts through the extraneous baggage of ego and image that he sees clogging up the independent film scene in this country. Probably his most crucial departure from the norm comes through the way he works with actors to develop their characters and stories. In the case of the Tenderloin-birthed poolhall drama Chalk he brought nonprofessional actors like Earl Watson and Johnny Reese together with local pros like Kelvin Han Yee and longtime Nilsson collaborator Don Bajema. It worked extremely well, and not surprisingly created a story that feels oh-so-Frisco in its composition.

On my to-see wish list: Crumb, another of the titles I missed last year.

the 2000s: In the Bathtub of the World (Caveh Zahedi, 2001)

This week Zahedi's hybridized documentary I Am a Sex Addict is playing the Balboa's other screen, but it would fit right into the series, as it was partially set in Frisco and uses local locations to stand in for Paris and elsewhere. But his earlier In the Bathtub of the World is a Frisco film (video again, really) with an even more radical approach. It proposes that a filmmaker does not need to go out and capture or create a particular story, but can make an important, inspiring film capturing some of the very essence of life just by turning a camera back on himself or herself. If a View to a Kill, Vertigo and even Greed use Frisco as the backdrop of the director's vacation film, In the Bathtub of the World turns the home movie of a Frisco resident into something at least as large and profound. Here's a fascinating thing I found that helps to explain why not everybody's heard of it.

On my to-see wish list: the Bridge, Eric Steele's controversial new doc on the topic of Golden Gate Bridge suicides. Another consideration of the subject, the Joy of Life by Jenni Olson, was a highlight of last year's SFIFF (and plays again at the PFA this Tuesday) I expect Steele's film to be of a completely different sort, but my expectations are still high. It's playing at three screenings in this year's edition of the festival, on April 30-May 2.

On my to-see wish list: the Bridge, Eric Steele's controversial new doc on the topic of Golden Gate Bridge suicides. Another consideration of the subject, the Joy of Life by Jenni Olson, was a highlight of last year's SFIFF (and plays again at the PFA this Tuesday) I expect Steele's film to be of a completely different sort, but my expectations are still high. It's playing at three screenings in this year's edition of the festival, on April 30-May 2.

The post title is a bit of a misnomer, as Frisco Bay has been a motion picture hotbed for more than ten decades. It all began when Edward Muybridge first successfully photographed a horse's gallop for Leland Stanford in 1878. I've seen interesting Frisco films made in every decade since the Lumiere Brothers invented film exhibition in 1895, starting with 1897's Return of Lifeboat and including 1905's a Trip Down Market Street Before the Fire, which was shown at the PFA last weekend and I suspect might be among the films shown this Tuesday at 7PM as part of the Balboa's "City Quakes" earthquake centennial commemoration program. But I will start this list formally with the decade where films first grew to running times similar to those we expect today:

The post title is a bit of a misnomer, as Frisco Bay has been a motion picture hotbed for more than ten decades. It all began when Edward Muybridge first successfully photographed a horse's gallop for Leland Stanford in 1878. I've seen interesting Frisco films made in every decade since the Lumiere Brothers invented film exhibition in 1895, starting with 1897's Return of Lifeboat and including 1905's a Trip Down Market Street Before the Fire, which was shown at the PFA last weekend and I suspect might be among the films shown this Tuesday at 7PM as part of the Balboa's "City Quakes" earthquake centennial commemoration program. But I will start this list formally with the decade where films first grew to running times similar to those we expect today:the 1910s: The Tong Man (William Worthington, 1919)

Japanese-American screen idol Sessue Hayakawa played a Chinese anti-hero in this studio set-bound and somewhat sensationalistic depiction of the Frisco Chinatown underworld. It's no masterpiece and I wonder if there was even a single ethnically Chinese actor or crewman on set (most or all the Chinese parts were played by Japanese or white actors, which was customary for the time period) who could speak up against the film's stereotyping. Still, it's a fascinating curio and Hayakawa gives a typically strong performance.

On my to-see wish list: the Chaplin Essanay film a Jitney Elopement.

the 1920s: Greed (Erich Von Stroheim, 1924)

the 1920s: Greed (Erich Von Stroheim, 1924)Von Stroheim gained a reputation as one of the first advocates for film realism in large part through his desire to shoot his version of Frank Norris's novel McTeague in the Frisco where Norris had lived and, as Jonathan Rosenbaum points out, "scouted locations" for his story of a love triangle doomed by the sudden appearance of wealth. A masterpiece in its own right, Greed also feels like a primer on making Frisco locations (in this case the corner of Hayes and Laguna, the Cliff House, and dozens more) work to the advantage of a great film, one that surely influenced future directors trying the same trick like Orson Welles (see below). The studio cut (not Stroheim's original 47-reel version now lost, or Rick Schmidlin's digital "recreation") played the Balboa series last year.

On my to-see wish list: Lon Chaney surviving the Great Quake in the Shock.

the 1930s: San Francisco (W.S. Van Dyke, 1936)

I had never seen the most famous film about the 1906 Earthquake until the Balboa played it last April for the 99th anniversary of the event. Now it's being brought back April 16-18 for the 100th, and if you live in the area and have never seen it before you really ought to. Though this film, directed by Woodbridge Strong Van Dyke (aka "One Take Woody"), has a not wholly undeserved reputation for stodgily moralizing, it really is a grand entertainment nonetheless. I like to think of it as the movie that represents to Frisco what Gone With the Wind is for Atlanta: It's a big-budget, star-laden special effects extravaganza that distorts history through a potentially worrying lens, but it also treats The City as the center of the Universe. If you, like me, think of Frisco as a better candidate for that honor than Ted Turner's town, you'll almost certainly like San Francisco better than the even more famous picture Clark Gable made three years later. And perhaps this film's conservative reputation has been overblown too; the Terry Diggs piece I linked to convincingly argues that the film was covertly packed by screenwriter Anita Loos with pro-labor jabs against the MGM hegemony.

On my to-see wish list: the Howard Hawks Barbary Coast, which plays the Balboa on a bill with Pal Joey April 23-24.

the 1940s: the Lady From Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1947)

You may need to be automatically predisposed to Welles to be able to get over his silly brogue and fully enjoy this film, the only one he made with his then-wife Rita Hayworth, but there's no denying the power of the scenes that make use of some of the eeriest Frisco locations imaginable, now all the eerier because these places are no longer with us. I'm speaking particularly of Playland at the Beach, where this loopy noir ends in an especially bizarre fashion, and the murkily-lit halls of the recently demolished Steinhart Aquarium, where the (by this point in the Welles-Hayworth marriage) fictional-only lovers rendezvous and talk about a doubly-impossible future together. If the story doesn't totally hang together it certainly doesn't matter when Welles is making use of such dream-logic images as moray eels and funhouse mirrors to make an end run around the glib symbology often found in Hollywood classicism. I didn't see this film when it played in last year's Balboa series, but I've seen it several times, most memorably a few years ago at an outdoor screening in New York City's Bryant Park; admittedly this film is just as much a New York movie as a Frisco movie, but Frisco gets the last word.

You may need to be automatically predisposed to Welles to be able to get over his silly brogue and fully enjoy this film, the only one he made with his then-wife Rita Hayworth, but there's no denying the power of the scenes that make use of some of the eeriest Frisco locations imaginable, now all the eerier because these places are no longer with us. I'm speaking particularly of Playland at the Beach, where this loopy noir ends in an especially bizarre fashion, and the murkily-lit halls of the recently demolished Steinhart Aquarium, where the (by this point in the Welles-Hayworth marriage) fictional-only lovers rendezvous and talk about a doubly-impossible future together. If the story doesn't totally hang together it certainly doesn't matter when Welles is making use of such dream-logic images as moray eels and funhouse mirrors to make an end run around the glib symbology often found in Hollywood classicism. I didn't see this film when it played in last year's Balboa series, but I've seen it several times, most memorably a few years ago at an outdoor screening in New York City's Bryant Park; admittedly this film is just as much a New York movie as a Frisco movie, but Frisco gets the last word.On my to-see wish list: I Remember Mama, based on the book I remember my mama reading to me as a kid.

the 1950s: Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

What to say about this film I often consider the greatest of all time? I've seen it too many times to be surprised by its basic plot structure like I was the first four or five times I saw it, always suckered in by the false first climax. But each time I'm still surprised by another Hitchcockian touch I notice, little things like how Pop Liebel's nostalgia for "the power and the freedom" associated with manhood helps Scottie give himself permission to resist the post-war modernization of gender relations and throw himself into an old-fashioned romantic melodrama. And I'm always struck by another glimpse of the Frisco that existed before I was born but am slowly trying to understand. I've had this site on my sidebar since starting this blog, and if you've never taken the time to lose yourself in it for a while, how about now?

On my to-see wish list: the National Film Registry-selected D.O.A., which plays at the Balboa with another noir, the Bigamist, April 25th.

the 1960s: the White Rose (Bruce Conner, 1967)

I first planned this list to be entirely made of feature films, but once I thought of this experimental documentary short, I had to bump the Birds (at the Balboa April 21-22) or Take the Money and Run (April 26-27) or whatever else I was considering for this decade. It's the first Bruce Conner film I ever saw, back in 1996 at the old DeYoung Museum when it was showcasing art of the Beats. The centerpiece of the exhibit was Jay DeFeo's painting/sculpture the Rose, which she applied 2,300 pounds of oil paint to over the course of eight years before removing it by forklift from her apartment at the Pacific Heights section of Fillmore Street. Conner lived nearby and was on hand to film the extraction, which he edited into this beautiful seven minute piece accompanied by music from Miles Davis's Sketches of Spain.

On my to-see wish list: Experiment in Terror, the classic Blake Edwards thriller I missed when the Balboa showed it last year.

the 1970s: the Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)